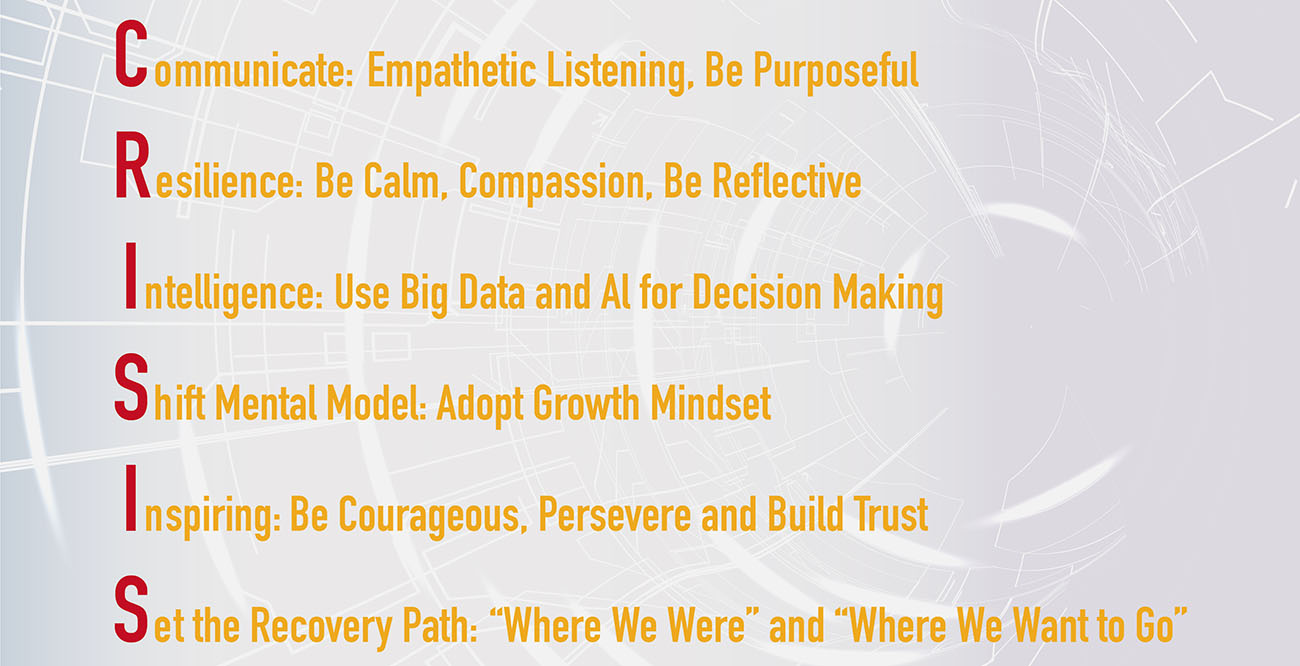

The “C.R.I.S.I.S.” Leadership Model

COMMUNICATE

Crisis communications from leaders often hit the wrong notes. Time and again, we see leaders taking an overconfident, upbeat tone in the early stages of a crisis—and raising stakeholders’ suspicions about what leaders know and how well they are handling the crisis. Authority figures are also prone to suspend announcements for long stretches while they wait for more facts to emerge and decisions to be made.

Neither approach is reassuring. As Amy Edmondson recently wrote, Transparency is “job one” for leaders in a crisis. Be clear about what you know, what you don’t know, and what you are doing to learn more. (Edmondson 2020)

Thoughtful, frequent communication shows that leaders are following the situation and adjusting their responses as they learn more. This helps them reassure stakeholders that they are confronting the crisis. Leaders should take special care to see that each audience’s concerns, questions, and interests are addressed. Having members of the crisis response team speak firsthand about what they are doing can be particularly effective.

Communications shouldn’t stop once the crisis has passed. Offering an optimistic, realistic outlook can have a powerful effect on employees and other stakeholders, inspiring them to support the company’s recovery.

The DLI research has found that inspiring and transformational leaders during times of crisis tend to seek out and act on the counsel or advice of others. They also have a team of advisors that can offer as many perspectives as possible on their situation, be it organizational or leadership challenges.

It is never easy to communicate bad news with the inherent risk of unsettling key stakeholders. In the context of a crisis such as COVID, it is tempting to talk down the threat to the organization. However, these leaders owe it to their stakeholders to provide honest depictions of reality and to be as clear as possible about known facts as well as “known unknowns.” Attempts to underplay the threat will undermine the credibility of future communications, as well as the trust that is integral to successful organizational culture.

Aside from dealing with bad news, communication more broadly is a critical aspect of leading during a crisis. It is important to communicate early and frequently, even with incomplete information. Strong public speaking and motivational skills are a vital part of a leader’s skill set but these are particularly important in a crisis. Communications must also have some positivity and hope for the future to motivate stakeholders and direct their energy. This may be viewed as bounded optimism.

After seeing Marriott’s revenue fall by nearly 75 percent in most markets because of COVID-19, CEO Arne Sorenson wanted to deliver a video message to employees. His team advised against it because of his appearance: He had been undergoing treatment for pancreatic cancer, and chemotherapy had left him bald. Sorenson made the video nonetheless. In it, he announced that he and the company’s chairman would forgo their salaries in 2020 and that the executive team’s compensation would be halved. He choked up at the end while talking about supporting Marriott associates around the world (Aten 2020). The video has inspired other leaders to give up their salaries too (Sundheim 2020).

Communicating clearly and often during a crisis is essential, but can be difficult. A leader has some advantage if the organization’s crisis management action plan (CMAP) has set up some communication guidelines. With or without a guide, however, the bottom line is simple: Keep internal and external communication lines open and working so that everyone is informed and they don’t have to make up their own stories about the crisis.

Based on the seriousness of the crisis (i.e., the perceived level of the crisis), the organization’s senior leaders must also decide who should be informed, when, and how. These stakeholders might include the organization’s employees, community groups, local government leaders and officials, government regulators, stockholders, customers, suppliers, the local neighborhood, and the news media.

From the outset of the crisis, senior leaders should be out among the employees sharing what they know has occurred, explaining what is being done about it now (and what steps are being taken so it won’t happen again), and, when possible, describing implications for the future. Leaving employees out of the information loop during a crisis can be a major mistake. An organization’s employees are a loud voice for the organization. They will undoubtedly tell their immediate circle of influence what they think happened, based on what they know. Their knowledge can be the truth that they heard from their leaders or it can be the rumors and gossip they heard in the hallway. If they are not told what is going on, their fears and anxieties about the crisis can turn into anger, distrust, and even revenge. And the organization will become the target of these emotions and possibly destructive behavior.

Many consider New Zealand a success story in its handling of COVID- 19. Prime Minister Arden’s communication concerning COVID-19 has been exemplary. In the context of the early lockdown, by directing people to “stay home to save lives,” the prime minister succinctly offered real purpose to her direction. While giving direction, this early communication also involved meaning, as Arden was creating a narrative around how New Zealand would work together to overcome the threat of COVID (Friedman 2020). Similarly, the way Arden addressed the nation from home—wearing casual clothes and with a child’s toys in plain sight—at a time of national lockdown was a great example of showing empathy and identifying with her citizens (Ardern 2020).

What the organization’s leadership initially communicates to the organization’s internal and external stakeholders should include (and generally be limited to) the known details of the situation, what went wrong and why, what is being done to deal with the immediate situation, and the actions that are and will be taken to ensure the situation does not happen again. Leaders should stick to the facts and avoid conjecture. In the early stages of the crisis, it is also wise to avoid speculating about the future implications of the crisis. If pressed, leaders can say that the greater implications are unknown at present but will be analyzed. Under no circumstances should leaders fabricate or change information with the intent to deceive. Such actions will certainly be found and exacerbate the crisis.

There are immediate and specific communication actions that leaders can take to reduce the negative impact of the crisis and also sustain (and perhaps even improve) relationships with stakeholders. Some of the most important external stakeholders during a crisis are the media; and clear, consistent communication with them is critical during a crisis. The news media can extend the leader’s communication resources. If handled correctly, a leader can use the media to exert a powerful, positive, emotional impact on all stakeholders, and in particular on the organization’s employees.

The best practices adopted by these leaders include asking themselves the following questions:

- “Do I have access to diverse voices and sources of information?”: They adopt scenario planning to determine whose knowledge or expertise they might need in various kinds of crises and identify whether their organization currently has access to it.

- “Do I routinely consider other team members’ ideas or feedback when making decisions?”: They sought out expertise to fill their blind spots and make informed decisions. Effective crisis leaders are those who know when—and how—to defer to others.

- “What systems or processes might I put into place to surface and capture others’ perspectives?”: They look at how communication is structured within their organization and whether there are barriers or silos that they need to proactively address.

RESILIENCE

The well-being and resilience of self and others are more important now than ever before. Role modeling around well-being will be important for leadership success as well as the need for clear messaging on psychological first aid, well-being, and mental health from the business.

These leaders in the middle of a crisis are faced with a flurry of urgent issues across what seems like innumerable fronts. Resilient leaders zero in on the most pressing of these, establishing priority areas that can quickly cascade.

An essential focus in a crisis is to recognize the impact the uncertainty is having on the people that drive the organization. The priority should be safeguarding workers, ensuring their immediate health and safety, followed by their economic well-being. At such times, emotional intelligence is critical. In everything they do during a crisis, resilient leaders express empathy and compassion for the human side of the upheaval, for example, acknowledging how radically their employees’ priorities have shifted away from work to be concerned about family health, accommodating extended school closures, and absorbing the human angst of life-threatening uncertainty. Resilient leaders also encourage their people to adopt a calm and methodical approach to whatever happens next.

Credibility is a valuable leadership commodity during a crisis. It’s built on consistency, but consistency isn’t just the ability to do the same thing over and over. It’s also the ability to spring back from negative comments and adapt to rapid changes, to be resilient.

Mary Lynn Pulley and Michael Wakefield (2001) write in Building Resiliency: How to Thrive in Times of Change that resiliency is important because change is so pervasive. It’s hard to imagine change as dramatic as that brought about by chaos, and resiliency creates a continuity of effective leadership around which people in an organization can rally.

Leadership consistency is like the smooth ride of a well-engineered car—the car’s suspension system adapts to the bumps in the road to protect the passengers and provide stability. In the same way, a leader who can handle change and difficulty with flexibility, courage, and optimism protects others in the organization, provides stability in a tumultuous environment, and inspires trust.

Resiliency is a reflection of the mental toughness required to keep your leadership on the road and moving forward during the twists and turns of a crisis. During a crisis, leaders at all levels are faced with all kinds of extremely unpleasant possibilities, such as serious injury to themselves or others, the destruction of property and equipment, or worse. They must be resilient and mentally tough enough to handle the situation. There can be no indifference or resignation. When the leader hangs tough, it shows others in the organization that someone cares enough about them and their welfare to take the punishment and to keep springing back. To quit or resign is not an option because it would result in the loss of all influence and credibility.

Agility

While much of the above is self-explanatory, the need for agility when facing future crises is especially important. One positive phenomenon of the crisis has been the speed at which the leaders of many of these organizations have accelerated their uptake of technology, built resilience into their supply chains, and created alternative revenue streams. Some of these changes, such as Unilever shifting from the production of skin care products to cleaning and hygiene products, were simply demand-driven. In other cases, these have been to develop or expand online distribution channels and/or move from B2B to B2C models. While many of these pivots are an extension of existing capacity and are aligned with the organization’s strategy, some might be permanent. Importantly, the agile decision making that leads to these shifts needs to be embedded into the organizational DNA as organizations set the path to recovery.

Agility and resiliency are highly correlated concepts and both are essential for adapting to disruption and times of crisis. It is important to understand that they are not the same, yet they are often confused in management literature and also by business leaders and practitioners.

Several decades ago, businesses were built to last. The successful companies were the stable companies—those that consistently, dependably offered a product or service desired by the masses. The goal for those running these businesses was to eliminate uncertainty, complexity, and variability where possible.

Lengthy, tedious planning cycles and bureaucratic processes are hallmarks of this type of business. The uncertainty in complex projects is dealt with by planning experts who would attempt to predetermine every possible detail before implementation. Success is measured by the extent to which the plan is followed and predetermined milestones are achieved. While a traditional approach to business management persists in some types of organizations today, it is often being replaced by a more dynamic, agile approach.

Today, businesses are built to change. Rather than being viewed as problems to eliminate, complexity, uncertainty, and dynamism are seen as inevitable factors involved in meeting the ever-changing customer demands. The most successful organizations are those able to constantly evolve to continuously add value to their customers’ lives.

Today’s hyper-competitive world can be a tough place for many businesses. Large companies are always looking to produce better products while reducing costs, customers’ needs evolve, and the world economy fluctuates at large. In a sentence, your business will face many threats. But how do you survive?

A successful business knows when to bend, pivot, and change to accommodate forces more powerful than itself, a process that requires business agility. Business agility can be used to adjust to market changes in addition to internal business changes.

Business agility refers to the company’s ability to quickly adapt to changes and fluctuations in its business environment. The faster a company can adjust its business strategy, the higher its business agility. Business agility is an organizational method to help businesses adapt quickly to market changes that are either external or internal. If a business is set up to respond rapidly and with the flexibility to meet customer demands, they’re more likely to thrive and keep those customers.

Resilient organizations are those that rebound and prosper after business disruption because they’re adaptive, agile, and sustainable. Resilient organizations have resilient leaders who see change as opportunities for continued growth rather than a source of anxiety and fear. Response, recovery, and contingencies are the basis of resilience.

To achieve organizational high performance in an era of constant disruption and crisis, both agility and resilience are important. This author defines both terms as follows:

Agility refers to the ability to make a rapid change and achieve flexibility in various aspects of the operations, in response to changes or disruptive events in the external environment that could be characterized as a volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous, and disruptive (VUCAD) environment. It can also be viewed as the capacity for responding with speed and flexibly and decisively toward anticipating, initiating, and taking advantage of opportunities and avoiding any negative consequences of change.

Resilience refers to the ability to anticipate, prepare for, and recover from disasters, emergencies, and other disruptions, and protect and enhance workforce and customer engagement, supply network and financial performance, organizational productivity, and community well-being when disruption occurs. It can also be viewed as the capacity for resisting, absorbing, and responding, even reinventing, if necessary, in response to fast and/or disruptive change that cannot be avoided such as the “black swan” events.

Leaders should also explore opportunities for developing collective agility where major challenges require entire systems to be agile and adaptable. Such challenges require whole-system collaboration and design rather than piecemeal solutions. The accelerated delivery of COVID vaccines in the United States is a recent illustration of whole-system design and collaboration across all stakeholders in the system. This ranges from manufacture, regulatory approval, vaccine distribution and tracking, supply chain coordination, and a range of healthcare systems and pharmacies. There are many advantages to encouraging a horizontal and vertical cross-section of the system to codesign the strategic outcomes as well as the business model and tactics. These include an outside-in perspective, facilitation of buy-in, identifying bottlenecks and problems early, and quicker decision making (Deloitte 2020a).

One major challenge may be the tension between traditional governance structures and processes that often focus on risk. Another may be fixed processes and the speed and agility required to take up opportunities in the new environment. Accordingly, governance structures and processes may need to adapt.

INTELLIGENCE (Business Intelligence and Data Analytics)

When Harvard Business Review investigated why some companies had reached new levels of success in the years following the Great Recession of 2008–2010, the researchers concluded preparation was the differentiating factor (Gulati, Nohria, and Wohlgezogen 2010).

Crises change markets, industries, and economic processes. Hence the key to success is change management. One of the best ways to manage change is by making wise decisions about debt, workforce management, and new technologies. The best way to improve business decision making is by supporting those decisions with advanced data analytics.

In times of crisis, business intelligence (BI) is an area that leaders can leverage successfully when revenues are decreasing and budget problems come into play. By leveraging BI and big data analytics, leaders will be able to discover things that are not obvious or that they didn’t know, such as the root cause of those revenue drops and how they affect specific levers within their organization.

Data Analytics

Data analytics is an emerging field in the 21st century when using analytical tools has become a fundamental part of the business decision-making process, including operations on crisis management. The exponential growth of data, with technological advancement, inspires the creation of devices such as smartphones and the development of space technologies. As a result, the amount of information generated from these devices and technologies is surging, leading to the so-called big data, which has become a disruptive element in the workforce. Data analytics has been demonstrated to be an asset to identify patterns, predicting outcomes, and guiding corporate strategies (Ngai, Xiu, and Chau 2009).

Data analytics is a set of analytical and functional tools to gain insights into business processes and uncover hidden patterns from the BI view. It is the use of data, obtained from different sources, via statistical and quantitative analysis, explanatory and predictive models, and factbased management to guide the decision making and activities of the stakeholders (Davenport and Harris 2007). It is a collection of theories and technologies that turn raw data into relevant and usable information for day-to-day operations, based on the analysis of datasets to deduce the information found within them. Some business questions can be answered to find potential prospects that will give a company a competitive edge in the market. These are “what happened?” in a descriptive sense, “why did it happen?” in a diagnostic sense, and “when might it happen?” in a predictive sense.

Data-driven decision making is observed as an essential part of business operations. It is achieved by extracting descriptive insights to observe current operations, predictive insights to forecast possible future events, and prescriptive insights to execute business strategies. Effective planning is a critical factor for allocating the necessary resources with minimal cost and time. The indicators that are gathered from the computational models are part of the crisis and risk management to be ready for any outcome. These insights can show an upcoming systemic risk, such that allocating resources will avoid these downturns or delay the losses.

Proper risk management is critical for each company during difficult times. Analytics can be used to manage business continuity and retention by monitoring, forecasting, and preparing for crisis management and incorporating them into the strategy. The decision-making process is an important aspect of business that affects economic development and the long-term viability of the business in the external environment it operates.

The use of business analytics in a data-driven setting shows that there is a way to enhance management capability by offering valuable insights. These observations will pave the way for a good business strategy that puts them ahead of the competition. Because of advancements in information technology, data analytics has enabled service technology systems to create innovative ways to respond to customer needs.

Business Intelligence

BI is a computer-supported system used for identification and to produce new insights and high-quality knowledge to support decision making (Božič and Dimovski 2019). BI is learning from the business experience, which explains the behavioral approach to using informatics and information technology to make decisions. It is an important part of organizational planning to gain intuitive sight and to execute the operations

phase by phase based on these informal gatherings. Knowledge workers and data scientists are essential for each company to establish its corporate strategy and planning.

BI is a sequence of operational processes to provide the right information in the right format and to represent such information to the consumer in real time. Intelligent decision support systems and knowledge management databases are part of these advanced evolutionary stages. The multilayer framework is promoted by casual interdependencies and the holistic design of business analytics. BI systems’ maturity is based on information content quality, information access quality, analytical corporate culture, and the use of information for decision making.

Data analytics can be used to evaluate these risks, known as black swan events, where the value creation would be preserved while focusing on evaluating contingencies that threaten the present business model.

Organizational ambidexterity is the ability to respond to changes in the business environment where each firm may encounter environmental ambiguity, which is defined as instances when business relationships are unclear because of a lack of information. A firm needs to achieve organizational ambidexterity when it faces a competitive environment.

This requires companies to recognize new information to adjust dynamic capabilities while focusing on internal and external changes. Dynamic capabilities of the organizations evolve with sensing new opportunities that can influence organizational decision making. Competitive advantage is derived from a firm’s ordinary capabilities that have been transformed through these decision capabilities.

During the DLI research, it was found that the organizations leveraged data analytics to enhance their dynamic strategic capability in corporate planning during these systemic risks and crises. It helps these organizations understand uncertain economic environments to stay competitive while the focus is on day-to-day operations. The business cycles are directly affected by value creation where the agile frameworks play a factor.

Most organizations have crisis management teams, protocols, and business continuity to guide current actions and forecast possible responses to future events including pandemics and unexpected downturn risks. These policies need to reduce business-critical operations and travel, distribute all critical operations across the departments for effective decision making, diagnose employees at work, or ask them to stay at home if they are sick.

Although the main emphasis is containing and mitigating the risk from these unexpected events themselves, during the COVID-19 pandemic, these companies established a corporate plan for unanticipated business risks and downturns. These actions include updating BI daily, necessitating new strategies of mitigation rather than containment, using experts’ knowledge and predictive forecasting understanding of what’s happening and will happen including epidemic and public health intelligence, and establishing resilience principles in developing policies that also include consistent communication with the employees and evolvability for preparedness for the next possible crisis. These policies for dealing with and resolving the ability to forecast immediate results are get-ready scenarios for current and future situations. Dealing with and resolving the immediate problems that COVID-19 presents to each company’s workforce as well as creating resilience protocols that can foresee similar cyclical events will enable businesses to continue operating throughout this pandemic crisis.

When dealing with black swan events like pandemics, data-driven decision making is a crucial tool, and predictive analytics can foresee similar catastrophes. Crisis management capacities of businesses will need to be more data-driven and based on forecasting technologies to prepare for probable pandemic-like situations.

Black swan is thought to be a systemic shock to financial markets and daily societal life that may change social standards. Data analytics are used in risk management as part of crisis management, where data-driven decision making is given top importance to control and prevent such disruptions.

SHIFTING THE MENTAL MODEL

Believing that your qualities are carved in stone––the fixed mindset–– creates an urgency to prove yourself over and over. If you have only a certain amount of intelligence, a certain personality, and a certain moral character, then you’d better prove that you have a healthy dose of them. It simply wouldn’t do to look or feel deficient in these most basic characteristics (Dweck 2006).

There’s another mindset in which these traits are not simply a hand you’re dealt and have to live with, always trying to convince yourself and others that you have a royal flush when you’re secretly worried it’s a pair of tens. In this mindset, the hand you’re dealt is just the starting point for development. This growth mindset is based on the belief that your basic qualities are things you can cultivate through your efforts, your strategies, and help from others. Although people may differ in every way––in their initial talents and aptitudes, interests, or temperaments–– everyone can change and grow through application and experience (Dweck 2006).

Those thriving leaders interviewed during the DLI research emphasized the importance of critical thinking, which helps them to establish situational awareness and impose effective strategy, direction, and action in situations that are exceptionally volatile and uncertain. In such circumstances, information available to decision makers is likely to be ambiguous. Also, there may be too much of it or too little, and what there is may appear to be unstructured, confusing, and possibly contradictory.

The situation is likely to be uncertain, and suitable courses of action may not be readily apparent or clear enough to support confident and effective decision making. However, this may be exactly when urgent choices and critical decisions have to be made. These leaders recognized these problems as characteristics of crises. They were able to leverage the business of managing information to establish situational awareness. This awareness, when shared with their crisis leadership team and key stakeholders, is the essential basis for effective choices of strategy, direction, and action. Shared situational awareness implies creating and maintaining a common understanding of what is going on, what that means (in terms of its implications), and what it might mean (in terms of reasonable deductions that can be made about future developments).

INSPIRING

Employees’ trust in their organization is vital during crises and disruptions. It powerfully facilitates employees’ ability to respond constructively to crises and change, and it underpins organizational agility and resilience. Yet it is during such episodes that trust is most threatened. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this conundrum has organizational leaders asking: How can we preserve employee trust in the face of the financial and other challenges posed by the outbreak?

Yet it is during crises and disruption—when trust is most required— that it is also more likely to be lost. The COVID-19 pandemic is posing just such a threat. It is requiring organizational leaders and policy makers to make rapid, large-scale changes to both sustain organizational viability and maintain the flexibility and ability to later scale up and rapidly return to their core business once the pandemic passes. To ensure organizational survival, they are having to make tough and unpopular decisions, such as cutting pay and work hours and laying off workers temporarily or permanently. The uncertainty and unpredictability of the pandemic have jolted employees out of their familiar ways, including their habitual trust in their employers, and has heightened their sense of vulnerability. In such a context, employees need and seek reassurance from their employer that their continued trust is deserved.

Leaders must take key practical actions to preserve trust. The DLI research shows that during crises, employee trust can not only be preserved but also be enhanced. These thriving leaders show that employees who feel a greater sense of connection are far more likely to ride out volatility and be available to help companies recover and grow when stability returns.

Central to reducing uncertainty is drawing on and reinforcing the familiar, established foundations of trust that already exist in the organization. These trust foundations are unique to each organization and include the values, purpose, relationships, practices, organizational structures, and processes that built and sustained employee trust before the crisis. For example, in one government agency we studied, trust was founded strongly on principles of fairness, integrity, and professional respect. In a manufacturing business, employee trust was based on a unionized culture and the strong relationships between line managers, workers, and trade unions at the local plant level. These trust foundations highlight what the organization needs to protect and continue to do to preserve employees’ trust.

We believe that all leaders can be inspirational during times of crisis as all they need to do is unlock their inspirational potential and find an opportunity to demonstrate their capability. They need to develop the relevant skills which they can learn, grow, and develop to increase their impact and influence on their followers. It is important to understand from the start that becoming an inspirational leader requires focused effort, practice, and the ability to conduct self-reflection. Inspiration is personal; our source of inspiration is closely linked to our beliefs, values, and identity.

Inspirational leadership is both a mindset and a skill. It should be thought of as an action-orientated mindset where one individual can ignite a fire in another person’s heart and/or mind and move a person or team of people to take action and achieve something greater than the current status quo. Inspirational leadership, at its core, is about finding ways to enhance the potential of those you lead in a way that works for them and inspiring others to push themselves, achieve more, and reach that potential. The methods by which this is done will vary from person to person, and business to business, but the outcome is always the same: People develop greater confidence in what they can do and apply this confidence in a way that benefits the organization they work for.

During times of crisis, when employees aren’t just engaged, but inspired, that’s when organizations see real breakthroughs. Inspired employees are themselves far more productive and, in turn, inspire those around them to strive for greater heights. The DLI research shows that while anyone can become an inspiring leader as it is believed that they’re made, not born, in most companies, there are far too few of them. Those thriving leaders are inspiring as they leverage effectively their unique combination of strengths to motivate individuals and teams to take on bold missions—and hold them accountable for results. And they unlock higher performance through empowerment, not command and control.

While the research found that leaders who inspire are incredibly diverse, which underscores the need to find inspirational leaders that are right to motivate your organization, there is no universal archetype. A corollary of this finding is that anyone can become an inspirational leader by focusing on his or her strengths. Although DLI found that many different attributes help leaders inspire people, it also identified that there is one common trait that indicated matters more than any other: mindfulness. This enables the leaders to remain calm under stress, empathize, listen deeply, and remain present.

SET THE RECOVERY PATH

One of the biggest questions employees have asked their leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic is when this coronavirus madness will end so that they can get back to normal or business as usual. The reality is that it is going to be business as unusual. To prepare for the “new normal” or the “next normal,” leaders need to answer the question “what can I do now to prepare for when things return to a new normal?” To achieve this, they need to reflect on what has happened and what lessons they have learned and then plan to start with a new vision.

They need to connect the conversation about why they and the leadership team are embarking on preparing the organization for the future, what the outcomes are likely to be, and how to go about it. Leaders need to stay firmly grounded in questions like “what’s our goal here? What does success look like for us?” Leaders need to build a culture of accountability, foresight, a “people-first ahead of process and technology” mantra, and decisive adaptability. For many organizations, this means asking their workforce to work from home. If you are preparing for increased remote work, ensure that the organization has in place the right technology and the technical capacity to support it, including bandwidth, VPN infrastructure, authentication, access control mechanisms, and cybersecurity tools that can support peak traffic demands. Many leaders have confessed that their organizations were not ready for this!

Reshaping the Organization for Recovery

Two important goals of leadership following a crisis are to rebuild and strengthen relationships (between the people in the organization and between the people and the organization) and to learn from the experience to prepare for the next crisis. In working toward those goals, one of the most effective things leaders can do after the crisis is to assure employees that the probability of the same crisis reoccurring is virtually nonexistent. Otherwise, anxiety levels will remain high in the organization and significantly impact morale and productivity. Leaders at all levels should talk to employees and personally share what preventive measures are being taken to avert another crisis. This allows the employees to ask questions, an act that can be therapeutic and calming.

Another more formal but particularly effective means of providing such reassurance is through updated and highly publicized company rules and regulations aimed at preventing a similar crisis. These revised rules can outline improved crisis assessment procedures, including early warning and detection, crisis indicators, and improved interpersonal communication methods among leaders and employees in general.

These assurances can be the first step in rebuilding and reviewing the organization’s communication strategies. Clear and continuing communication is as essential after a crisis as it is before and during a crisis. Making sure those lines are open after a crisis helps leaders and the organization as a whole to learn from their experience and enhance their capability to deal with future crises. It also helps employees connect to the organization and connect and strengthen the bonds they developed during the crisis.

Reference: Sattar Bawany (2023), Leadership in Disruptive Times: Negotiating the New Balance. Business Expert Press (BEP) LLC, New York, NY. Abstract available at: https://www.disruptiveleadership.institute/second-edition-book/