Introduction

Leadership transitions—whether they involve a first-time manager, a newly promoted executive, or an external hire assuming a critical role—represent pivotal moments in an organization’s leadership pipeline. These transitions, if managed effectively, can accelerate performance, foster engagement, and ensure strategic continuity. However, when mishandled, they pose significant risks, including decreased team morale, lost productivity, and leadership derailment. Recognizing the high stakes of leadership transitions, the Centre for Executive Education (CEE) has developed a structured Transition Coaching™ Framework to support leaders in navigating these critical inflection points successfully.

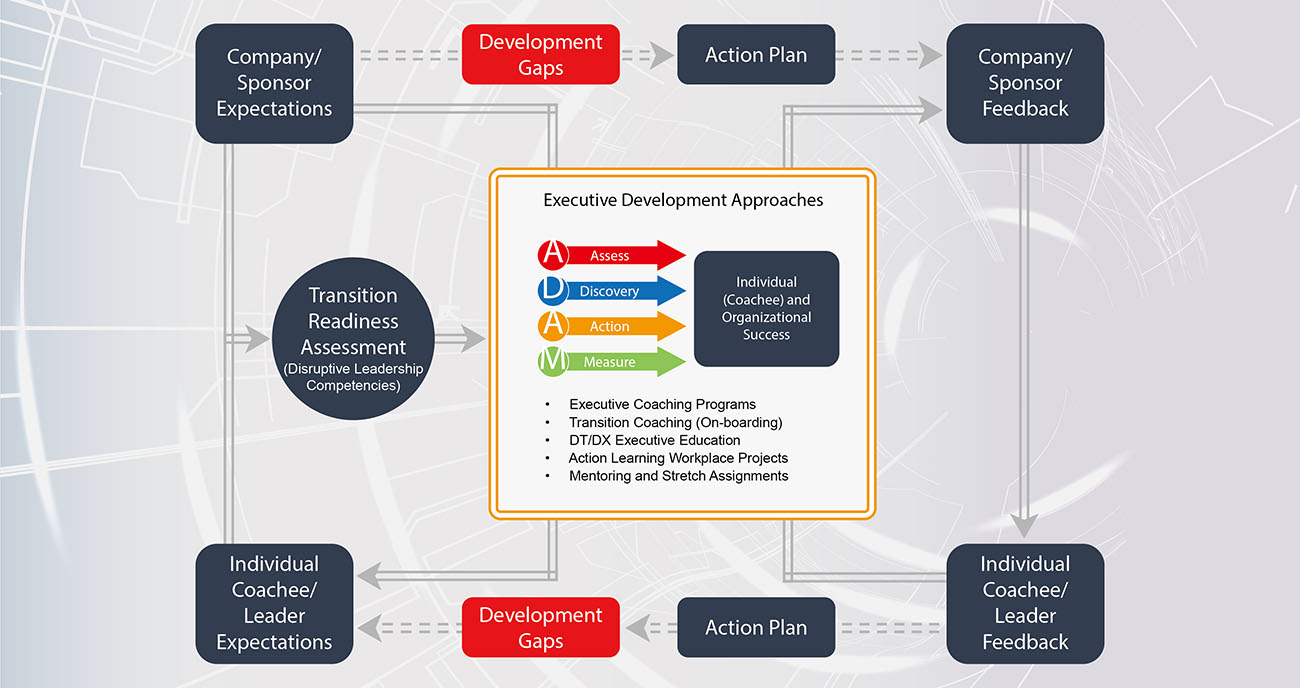

The Transition Coaching™ Framework is a systematic, evidence-based approach designed to accelerate the effectiveness of leaders taking on new roles, responsibilities, or contexts (see Figure 1). Grounded in leadership science and best practices in executive development, the framework aims to build confidence, clarity, and capability in transitioning leaders, thereby contributing to the development of a robust leadership pipeline and the achievement of sustainable organizational performance.

Figure 1: The Transition Coaching™ Framework

Accelerating Leadership Effectiveness

The early days of a new leadership role are crucial. The Transition Coaching Framework supports leaders in clarifying role expectations, aligning with key stakeholders, and identifying early wins. Through structured coaching sessions, new leaders gain deeper self-awareness, understand the strategic landscape, and develop a 90-day transition plan that aligns with both personal strengths and organizational goals.

By focusing on adaptive thinking, influence strategies, and relationship building, the framework helps transitioning leaders navigate cultural nuances and avoid common pitfalls. This focused support leads to faster integration, better decision-making, and stronger team engagement—critical factors for sustained performance.

Strengthening the Leadership Pipeline

A consistent and structured transition coaching process enhances an organization’s ability to develop internal talent and promote from within. By preparing future leaders for the challenges of new roles, organizations reduce the risk of failure in role transitions and increase the likelihood of long-term leadership success.

Moreover, the framework encourages succession readiness by embedding leadership competencies into the development process. Leaders learn how to assess complexity, communicate vision, and mobilize teams, strengthening their readiness for broader responsibilities. This supports the cultivation of a resilient, future-ready leadership bench.

Driving Organizational Agility and Sustainability

In today’s volatile and uncertain environment, organizations must be agile in responding to change. Leaders in transition often face shifting priorities, stakeholder expectations, and external disruptions. The Transition Coaching Framework equips them with the tools to lead through ambiguity, build trust quickly, and deliver results under pressure.

By ensuring leaders are equipped to succeed from the outset, the framework minimizes disruption, maintains momentum, and reinforces organizational agility. This contributes to greaterstrategic alignment, employee engagement, and ultimately, sustainable performance.

Executive Coaching Versus Transition Coaching

Effective coaching is a major key to improving business performance. Executive coaching focuses on the qualities of effective leadership and improved business results. It is comprised of a series of structured, one-on-one interactions between a coach and an executive, aimed at enhancing the executive’s performance in two areas (Bawany 2018i, 2019a):

- Individual personal performance

- Individual organizational performance

When executives are first confronted by being coached, they are not always clear about how best to use their sessions and are quite unaware that it is they who set the agenda; in fact, some executives expect executive coaching to be like a one-on-one tailored training program where the executive coach initiates the agenda. Executive coaching teaches the beneficiary (coachee) to minimize, delegate, or outsource nonstrengths by changing ineffective behaviors or changing ineffective thinking (Bawany 2020).

The upfront purpose of executive coaching is to develop key leadership capabilities or focus required for their current role. But it can also be used as an instrument to prepare them for the challenges of the next level. The whole coaching experience is structured to bring about effective action, performance improvement, and personal growth for the individual executive, as well as better results for the institution’s core business (Bawany 2019a).

An executive coach only has one item on his agenda—the client’s success. This means going where it might hurt and keeping a client accountable for achieving their goals. Coaching helps people grow personally and as professionals. This growth allows them to commit completely to the success of an organization. When professional coaches work with organizations, they can turn performance management into a collaborative process that benefits both the employee and the organization (Bawany 2020).

While many executives are familiar with executive coaching and may even have enlisted the help of external coaches at some point, few understand the right type of coaching approach required to address the challenges faced by leaders in transition situations. Many newly placed executives fail within their first two years in the position for reasons ranging from their inability to adjust to a new role and develop strong relationships, to a lack of understanding of the business imperatives. What new leaders do during their 90 days in a new role greatly determines the extent of their success for the next several years (Bawany 2010).

What if there was a proven process to support new leaders in their role while significantly increasing return on investment and ensuring a positive economic impact for the organization? One such process is transition coaching, an integrated and systematic process that engages and assimilates the new leader into the organization’s corporate strategy and culture to accelerate productivity (Bawany 2007, 2010).

Transition coaching encompasses the goals of executive coaching but focuses on a specific niche, the newly appointed leader (either being promoted from within or being hired externally). Leadership transitions are among the most challenging situations executives face. Take the case of a leader who might enter a new position thinking he or she already has all the answers; or just the opposite, the leader might lack a clear understanding of what to expect from the role. The goal of transition coaching is to reduce the time it takes for new leaders to make a net contribution to the organization and establish a framework for ongoing success.

Those promoted from within will have to be mindful that a smooth and effective role-to-role transition is critical to the organization’s business performance. The organization depends on leaders to execute and meet objectives and has placed its bet that internal candidates are better valued and have less risk. Organizations understand that successful transitions ensure future capability (Bawany 2018i).

An unsuccessful transition can negatively impact an organization through poor financial results, decreased employee morale, and costly turnovers. So rather than risk this sink-or-swim gamble, organizations can improve the assimilation process through transition coaching (Bawany 2019a).

Transition coaching is also recommended when organizations assign managers to the role, for the first time, of leading digital transformation projects. If organizations use the right transition strategies, the leader will not only help prevent failure but also create additional value by accelerating the new leader’s effectiveness. Transition coaching engages the new disruptive leader in the organization’s corporate strategy and culture to accelerate performance.

The Potential Pitfalls of Leadership Transitions

The biggest trap that new leaders fall into is believing that they will continue to be successful by doing what has made them successful in the past. There is an old saying, “To a person who has a hammer, everything looks like a nail” (Bawany 2019a). So too it is for leaders who have become successful by relying on certain skills and abilities. Too often they fail to see that their new leadership role demands different skills and abilities. And so they fail to meet the adaptive challenge. This does not, of course, mean that new leaders should ignore their strengths. It means that they should focus first on what it will take to be successful in the new role, then discipline themselves to do things that don’t come naturally if the situation demands it (Bawany 2020).

Another common trap is falling prey to the understandable anxiety the transition process evokes. Some new leaders try to take on too much, hoping that if they do enough things, something will work. Others feel they have to be seen as “taking charge,” and so make changes to put their stamp on things. Still others experience the “action imperative”—they feel they need to be in motion, and so don’t spend enough time upfront engaged in diagnosis. The result is that new leaders end up enmeshed in vicious cycles in which they make bad judgments that undermine their credibility (Bawany 2018i, 2019a).

New leaders are expected to “hit the ground running.” They must produce results quickly while simultaneously assimilating into the organization. The result is that many newly recruited or promoted managers fail within the first year of starting new jobs.

From the extensive executive and transition coaching engagements over the past 20 years by the CEE’s panel of executive and transition coaches, it has been discovered that many newly promoted leaders in transition fail due to one or more of the following factors (Bawany 2019a):

- They do not fit into the organizational culture.

- They don’t build a team or become part of one.

- They are unclear about their stakeholder’s and their bosses’ expectations.

- They fail to execute the organization’s strategic or business plan.

- They lack savvy in maneuvering and managing internal politics.

- There is no formal process to assimilate them into the organization.

A proven assimilation process is critical as it provides support to the newly hired executive and helps the organization protect its investment.

Success Strategies for the Assimilation of New Disruptive Leaders

Successful new leaders redefine their need for power and control. Team members normally value a certain amount of freedom and autonomy. People want to influence the events around them and not be controlled by an overbearing leader. When the manager is an individual contributor, he or she is close to the work itself and is the master in control of his or her circumstances; the manager’s performance has a big effect on his or her satisfaction and motivation.

The situation is different when the managers are promoted and become a leader. Their contribution is less direct as they often operate behind the scenes. Leaders create frustration for everyone when they try to be involved in every project and expect team members to check in before beginning every task. World-class leaders delegate. They learn to trust. This means giving up some control. Leaders learn to live with the risks and know that someone else may do things a little differently. Every person is unique, and they will individualize certain aspects of their work. When leaders don’t empower and delegate, they can become ineffective and overwhelmed. In turn, team members feel underutilized and therefore less motivated (Bawany 2019a).

Finally, leaders learn to transition in other critical ways. They learn how to live with occasional feelings of separation and that people don’t always accept their decisions when faced with gut-wrenching situations. Leaders have a view of the big picture in mind. But the challenge for leaders lies in balancing the needs of many stakeholders: owners, employees, customers, and community. Because of this challenge, team members can feel alienated when unpopular decisions must be made. Leadership can be hard. It is impossible to please everyone all the time. While the need for belonging and connecting with the group is important, leaders know the mission and vision take precedence. Sometimes a leader should make waves, champion change, and challenge people’s comfort zone. Leaders may not always relish conflict, but they are not afraid of it either. Leaders are guided by standards, principles, and core values. Leaders focus on what is right, not who is right.

Leaders know they cannot make people happy. People have to take ownership and control of their happiness. Leaders do not focus on personality factors. At times, the individual self-interests of a team member may be in opposition to the interests of the group. Leaders concentrate on shared interests and team goals. Consequently, the driving force behind a team is a leader who treats team members with respect, while keeping the vision in mind. People are different and you have to treat people differently yet fairly (Bawany 2019a).

What Are the Skills Required for Disruptive Leaders in Transition?

In the literature and research on leadership transitions and helping leaders to accelerate themselves into new roles, early findings indicate that new leaders gain leverage by putting in place the right strategies, structures, and systems. Transitions could be viewed as an engineer would approach a challenging design problem: advising leaders to identify the right goals, developing a supporting strategy, aligning the architecture of the organization, and figuring out what projects to pursue to secure early wins (Bawany 2010, 2018i).

The current research and perspectives of the competencies and skills expected to be demonstrated by disruptive leaders (e.g., Bawany 2019a, 2020; Freakley 2019; Gibson, West, and Pastrovich 2020; Harvard Business Review 2015; Korn Ferry 2019; Mortlock et al. 2019; Wade, Tarling, and Neubauer 2017) include a combination of attributes and skills such as the ability to envision the future, agility, ESI skills such as empathy and relationship management (social skills), results driven, engagement, agility and adaptability, innovativeness and courage to experiment, and resilience.

ESI competencies such as empathy and social skills are essential building blocks in a disruptive leader’s ability to establish the right organizational climate when leading a digital transformation project and collaborating with various stakeholders. Leaders at all levels of the organization must constantly demonstrate a high degree of EI in their leadership roles. Emotionally intelligent leaders create a climate or a workplace environment of positive morale and higher productivity (Goleman 1998).

The reality confronting leaders in transition is that the relationships with their bosses, peers, direct reports, and external constituencies must be seen as good, to be a good source of leverage. These elevated relationships and the energy they can mobilize (or drain the leader) to the forefront can help leaders enter and gain momentum to meet the challenges of the new roles.

This is not to say, of course, that strategies, structures, and systems are unimportant; usually, they are critical. But if the new leader hopes to put in place the right strategies, structures, and systems, he or she must first secure victory on the relationship front. This means building credibility with influential players, gaining agreement on goals, and securing their commitment to devote their energies to helping the new leader achieve those goals.

In the leader’s new situation, relationship management or social skills are critical as they aren’t the only ones going through a transition. To varying degrees, many different stakeholders, both inside and outside the leader’s direct line of command, are affected by the way he or she handles his or her new role. Inside the new leader’s direct line of command are people who report directly to the leader, as well as employees from other groups. While some may feel apprehensive about the new leader’s arrival, all must adjust to the leader’s communication and managerial style and expectations (Bawany 2018i, 2019a).

Outside the new leader’s direct line of command are senior executives, peers, and key external constituencies such as customers, suppliers, and distributors. The new leader will likely have no “relationship capital” with these individuals, that is, there are no existing support or obligations upon which the leader could draw. The leader will need to invest extra thought and energy in gaining their support. Leverage through relationships is an essential foundation for effectiveness in a new leadership role.

Transition Coaching Approach for the Development of Disruptive Leaders

Transition coaching has three overall goals: to accelerate the transition process by providing just-in-time advice and counsel, to prevent mistakes that may harm the business and the leader’s career, and to assist the leader in developing and implementing a targeted, actionable transition plan that delivers business results (Bawany 2010, 2020).

While many of the issues covered by transition coaching are similar to those included in executive coaching, such as sorting through short- and long-term goals and managing relationships upwards as well as with team members, transition coaching is focused specifically on the transition and designed to educate and challenge new leaders. The new leader and coach will have to work together to develop a transition plan and a roadmap that will define critical actions that must take place during the first 90 days to establish credibility, secure early wins, and position the leader and team for long-term success (Bawany 2018i).

The transition coaching relationship also includes regular meetings with the new leader as well as ongoing feedback. Frequently, the coach conducts a “pulse check” of the key players, including the boss, direct reports, peers, and other stakeholders, after four to six weeks to gather early impressions so that the new leader can make a course correction if needed.

The transition coaching framework developed by the CEE with the complete transition coaching process provides new leaders with the guidance to take charge of their new situation, achieve alignment with the team, and ultimately move the business forward (Bawany 2020).

The “transition readiness assessment” is designed for the evaluation of the desired disruptive leaders’ competencies as stated earlier, which includes the ability to envision the future, agility, ESI skills such as empathy and relationship management (social skills), cognitive readiness, critical thinking, engagement, agility and adaptability, innovativeness and courage to experiment, and resilience, among others.

Conclusion

The Transition Coaching Framework by the Centre for Executive Education (CEE) provides a structured and impactful pathway for enabling leadership success during times of transition. By accelerating integration, developing critical capabilities, and aligning leadership actions with strategic goals, the framework strengthens the leadership pipeline and safeguards organizational performance. In an era where effective leadership is more critical than ever, structured transition coaching is not just a developmental tool—it is a strategic imperative for achieving long-term, sustainable success.

References

- Bawany, S. 2025. The Making of a C.R.I.S.I.S. Leader. New York, NY: Business Express Press (BEP) Inc. LLC.

- Bawany, S. 2023. Leadership in Disruptive Times: Negotiating the New Balance. New York, NY: Business Express Press (BEP) Inc. LLC.

- Bawany, S. 2020. Leadership in Disruptive Times. New York, NY: Business Express Press (BEP) Inc. LLC.

- Bawany, S. 2019a. Transforming the Next Generation of Leaders: Developing Future Leaders for a Disruptive, Digital-Driven Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Industry 4.0). New York, NY: Business Express Press (BEP) Inc. LLC.

- Bawany, S. 2018i. “Transition Coaching of Leaders for First 90 Days.” Leadership Excellence Essentials 35, no. 5, pp. 52–56.

- Bawany, S. 2010. “Maximizing the Potential of Future Leaders: Resolving Leadership Succession Crisis With Transition Coaching.” In Coaching in Asia—The First Decade. Candid Creation Publishing LLP.

- Bawany, S. 2007. “Winning the War for Talent.” Human Capital, pp. 54–57. Singapore Human Resources Institute.

- Freakley, S. 2019. “7 Skills Every Leader Needs in Times of Disruption.” The World Economic Forum.

- Gibson, P., K.W. West, and R. Pastrovich. 2020. Disruptive Leaders: An Overlooked Source of Organizational Resilience. Chicago, IL: Heidrick & Struggles Knowledge Center, Heidrick & Struggles International, Inc.

- Goleman, D. 1988. “What Makes a Leader?” Harvard Business Review, pp. 93–102. Harvard Business School Publishing.

- Harvard Business Review. 2015. “Driving Digital Transformation: New Skills for Leaders, New Role for the CIO.” Harvard Business Review. Analytic Services Report. Harvard Business School Publishing.

- Korn Ferry. 2019. The Self-Disruptive Leader. Korn Ferry Institute.

- Mortlock, L., A. Murphy, K.A. Razak, K. Ermelbauer, and I. Anderson. 2019. Transformation Leadership in a Digital Era. Ernst & Young LLP.

- Wade, M.R., A. Tarling, and R. Neubauer. 2017. Redefining Leadership for a Digital Age. IMD.